Download Free Apps & Games @ PHONEKY.com

Download Free Apps & Games @ PHONEKY.com

Subject: Issac Newton

Replies: 1 Views: 808

royal28 16.07.09 - 08:01am

Sir Isaac Newton

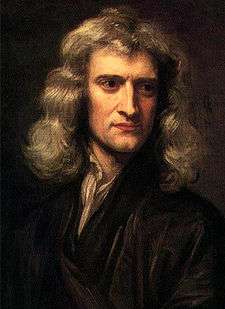

Godfrey Kneller's 1689 portrait of Isaac Newton (aged 46)

Born 4 January 1643(1643-01-04)

[OS: 25 December 1642][1]

Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth

Lincolnshire, England

Died 31 March 1727 (aged 84)

[OS: 20 March 1727][1]

Kensington, Middles*x, England

Residence England

Citizenship English

Nationality English (British from 1707)

Fields Physics, mathematics, astronomy, natural philosophy, alchemy, theology

Institutions University of Cambridge

Royal Society

Royal Mint

Alma mater Trinity College, Cambridge

Academic advisors Isaac Barrow[2]

Benjamin Pulleyn[3][4]

Notable students Roger Cotes

William Whiston

Known for Newtonian mechanics

Universal gravitation

Calculus

Optics

Influences Henry More[5]

Influenced Nicolas Fatio de Duillier

John Keill

Religious stance Arianism; for details see article

Signature

Notes

His mother was Hannah Ayscough. His half-niece was Catherine Barton.

Sir Isaac Newton, FRS (4 January 1643 31 March 1727 [OS: 25 December 1642 20 March 1727]),[1] was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian. His Philosophi Naturalis Principia Mathematica, published in 1687, is by itself considered to be among the most influential books in the history of science, laying the groundwork for most of classical mechanics. In this work, Newton described universal gravitation and the three laws of motion which dominated the scientific view of the physical universe for the next three centuries. Newton showed that the motions of objects on Earth and of celestial bodies are governed by the same set of natural laws by demonstrating the consistency between Kepler's laws of planetary motion and his theory of gravitation, thus removing the last doubts about heliocentrism and advancing the scientific revolution.

In mechanics, Newton enunciated the principles of conservation of both momentum and angular momentum. In optics, he built the first practical reflecting telescope[6] and developed a theory of colour based on the observation that a prism decomposes white light into the many colours which form the visible spectrum. He also formulated an empirical law of cooling and studied the speed of sound.

In mathematics, Newton shares the credit with Gottfried Leibniz for the development of the differential and integral calculus. He also demonstrated the generalised binomial theorem, developed the so-called Newton's method for approximating the zeroes of a function, and contributed to the study of power series.

Newton remains influential to scientists, as demonstrated by a 2005 survey of scientists in Britain's Royal Society asking who had the greater effect on the history of science, Newton or Albert Einstein. Newton was deemed the more influential.[7]

Newton was also highly religious, though an unorthodox Christian, writing more on Biblical hermeneutics than the natural science he is remembered for today.

Contents [hide]

1 Life

1.1 Early years

1.2 Middle years

1.2.1 Mathematics

1.2.2 Optics

1.2.3 Mechanics and gravitation

1.3 Later life

1.4 After death

1.4.1 Fame

1.4.2 Commemorations

1.5 Newton in popular culture

2 Religious views

2.1 Effect on religious thought

2.2 Views of the end of the world

3 Enlightenment philosophers

4 Newton and the counterfeiters

5 Newton's laws of motion

6 Newton's apple

7 Writings by Newton

8 See also

9 Footnotes and references

10 References

11 Further reading

11.1 Newton and religion

11.2 Primary sources

12 External links

Life

Early years

Main article: Isaac Newton's early life and achievements

Isaac Newton was born on 4 January 1643 [OS: 25 December 1642][1] at Woolsthorpe Manor in Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, a hamlet in the county of Lincolnshire. At the time of Newton's birth, England had not adopted the Gregorian calendar and therefore his date of birth was recorded as Christmas Day, 25 December 1642. Newton was born three months after the death of his father, a prosperous farmer also named Isaac Newton. Born prematurely, he was a small child; his mother Hannah Ayscough reportedly said that he could have fit inside a quart mug. When Newton was three, his mother remarried and went to live with her new husband, the Reverend Barnabus Smith, leaving her son in the care of his maternal grandmother, Margery Ayscough. The young Isaac disliked his stepfather and held some enmity towards his mother for marrying him, as revealed by this entry in a list of sins committed up to the age of 19: Threatening my father and mother Smith to burn them and the house over them.[8]

Newton in a 1702 portrait by Godfrey Kneller

Isaac Newton (Bolton, Sarah K. Famous Men of Science. NY: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1889)From the age of about twelve until he was seventeen, Newton was educated at The King's School, Grantham (where his signature can still be seen upon a library window sill). He was removed from school, and by October 1659, he was to be found at Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, where his mother, widowed by now for a second time, attempted to make a farmer of him. He hated farming.[9] Henry Stokes, master at the King's School, persuaded his mother to send him back to school so that he might complete his education. Motivated partly by a desire for revenge against a schoolyard bully, he became the top-ranked student.[10]

In June 1661, he was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge as a sizar--a sort of work-study role.[11] At that time, the college's teachings were based on those of Aristotle, but Newton preferred to read the more advanced ideas of modern philosophers such as Descartes and astronomers such as Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler. In 1665, he discovered the generalized binomial theorem and began to develop a mathematical theory that would later become infinitesimal calculus. Soon after Newton had obtained his degree in August of 1665, the University closed down as a precaution against the Great Plague. Although he had been undistinguished as a Cambridge student,[12] Newton's private studies at his home in Woolsthorpe over the subsequent two years saw the development of his theories on calculus, optics and the law of gravitation. In 1667 he returned to Cambridge as a fellow of Trinity.[13]

Middle years

Mathematics

Most modern historians believe that Newton and Leibniz developed infinitesimal calculus independently, using their own unique notations. According to Newton's inner circle, Newton had worked out his method years before Leibniz, yet he published almost nothing about it until 1693, and did not give a full account until 1704. Meanwhile, Leibniz began publishing a full account of his methods in 1684. Moreover, Leibniz's notation and differential Method were universally adopted on the Continent, and after 1820 or so, in the British Empire. Whereas Leibniz's notebooks show the advancement of the ideas from early stages until maturity, there is only the end product in Newton's known notes. Newton claimed that he had been reluctant to publish his calculus because he feared being mocked for it. Newton had a very close relationship with Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, who from the beginning was impressed by Newton's gravitational theory. In 1691 Duillier planned to prepare a new version of Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, but never finished it. However, in 1693 the relationship between the two men changed. At the time, Duillier had also exchanged several letters with Leibniz.[14]

Starting in 1699, other members of the Royal Society (of which Newton was a member) accused Leibniz of plagiarism, and the dispute broke out in full force in 1711. Newton's Royal Society proclaimed in a study that it was Newton who was the true discoverer and labeled Leibniz a fraud. This study was cast into doubt when it was later found that Newton himself wrote the study's concluding remarks on Leibniz. Thus began the bitter Newton v. Leibniz calculus controversy, which marred the lives of both Newton and Leibniz until the latter's death in 1716.[15]

Newton is generally credited with the generalized binomial theorem, valid for any exponent. He discovered Newton's identities, Newton's method, classified cubic plane curves (polynomials of degree three in two variables), made substantial contributions to the theory of finite differences, and was the first to use fractional indices and to employ coordinate geometry to derive solutions to Diophantine equations. He approximated partial sums of the harmonic series by logarithms (a precursor to Euler's summation formula), and was the first to use power series with confidence and to revert power series.

He was elected Lucasian Professor of Mathematics in 1669. In that day, any fellow of Cambridge or Oxford had to be an ordained Anglican priest. However, the terms of the Lucasian professorship required that the holder not be active in the church (presumably so as to have more time for science). Newton argued that this should exempt him from the ordination requirement, and Charles II, whose permission was needed, accepted this argument. Thus a conflict between Newton's religious views and Anglican orthodoxy was averted.[16]

Optics

A replica of Newton's second Refracting telescope that he presented to the Royal Society in 1672[17].From 1670 to 1672, Newton lectured on optics. During this period he investigated the refraction of light, demonstrating that a prism could decompose white light into a spectrum of colours, and that a lens and a second prism could recompose the multicoloured spectrum into white light.[18]

He also showed that the coloured light does not change its properties by separating out a coloured beam and shining it on various objects. Newton noted that regardless of whether it was reflected or scattered or transmitted, it stayed the same colour. Thus, he observed that colour is the result of objects interacting with already-coloured light rather than objects generating the colour themselves. This is known as Newton's theory of colour.[19]

From this work he concluded that the lens of any refracting telescope would suffer from the dispersion of light into colours (chromatic aberration), and as a proof of the concept he constructed a telescope using a mirror as the objective to bypass that problem. [20] Actually building the design, the first known functional reflecting telescope, today known as a Newtonian telescope[21], involved solving the problem of a suitable mirror material and shaping technique. Newton ground his own mirrors out of a custom composition of highly reflective speculum metal, using Newton's rings to judge the quality of the optics for his telescopes. By February of 1669 he was able to produce an instrument without chromatic aberration. In 1671 the Royal Society asked for a demonstration of his reflecting telescope.[22] Their interest encouraged him to publish his notes On Colour, which he later expanded into his Opticks. When Robert Hooke criticised some of Newton's ideas, Newton was so offended that he withdrew from public debate. The two men remained enemies until Hooke's death.[citation needed]

Newton argued that light is composed of particles or corpuscles, which were refracted by accelerating toward the denser medium, but he had to associate them with waves to explain the diffraction of light (Opticks Bk. II, Props. XII-L). Later physicists instead favoured a purely wavelike explanation of light to account for diffraction. Today's quantum mechanics, photons and the idea of waveparticle duality bear only a minor resemblance to Newton's understanding of light.

In his Hypothesis of Light of 1675, Newton posited the existence of the ether to transmit forces between particles. The contact with the theosophist Henry More, revived his interest in alchemy. He replaced the ether with occult forces based on Hermetic ideas of attraction and repulsion between particles. John Maynard Keynes, who acquired many of Newton's writings on alchemy, stated that Newton was not the first of the age of reason: he was the last of the magicians.[23] Newton's interest in alchemy cannot be isolated from his contributions to science; however, he did apparently abandon his alchemical researches.[5] (This was at a time when there was no clear distinction between alchemy and science.) Had he not relied on the occult idea of action at a distance, across a vacuum, he might not have developed his theory of gravity. (See also Isaac Newton's occult studies.)

In 1704 Newton published Opticks, in which he expounded his corpuscular theory of light. He considered light to be made up of extremely subtle corpuscles, that ordinary matter was made of grosser corpuscles and speculated that through a kind of alchemical transm*tation Are not gross Bodies and Light convertible into one another, and may not Bodies receive much of their Activity from the Particles of Light which enter their Composition?[24] Newton also constructed a primitive form of a frictional electrostatic generator, using a glas* globe (Optics, 8th Query).

Mechanics and gravitation

Newton's own copy of his Principia, with hand-written corrections for the second editionFurther information: Writing of Principia Mathematica

In 1677, Newton returned to his work on mechanics, i.e., gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets, with reference to Kepler's laws of planetary motion, and consulting with Hooke and Flamsteed on the subject. He published his results in De motu corporum in gyrum (1684). This contained the beginnings of the laws of motion that would inform the Principia.

The Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (now known as the Principia) was published on 5 July 1687 with encouragement and financial help from Edmond Halley. In this work Newton stated the three universal laws of motion that were not to be improved upon for more than two hundred years. He used the Latin word gravitas (weight) for the effect that would become known as gravity, and defined the law of universal gravitation. In the same work he presented the first an*lytical determination, based on Boyle's law, of the speed of sound in air. Newton's postulate of an invisible force able to act over vast distances led to him being criticised for introducing occult agencies into science.[25]

With the Principia, Newton became internationally recognised.[26] He acquired a circle of admirers, including the Swiss-born mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, with whom he formed an intense relationship that lasted until 1693, when it abruptly ended, at the same time that Newton suffered a nervous breakdown.[27]

Later life

Isaac Newton in old age in 1712, portrait by Sir James ThornhillMain article: Isaac Newton's later life

In the 1690s, Newton wrote a number of religious tracts dealing with the literal interpretation of the Bible. Henry More's belief in the Universe and rejection of Cartesian dualism may have influenced Newton's religious ideas. A m cript he sent to John Locke in which he disputed the existence of the Trinity was never published. Later works The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1728) and Observations Upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John (1733) were published after his death. He also devoted a great deal of time to alchemy (see above).

Newton was also a member of the Parliament of England from 1689 to 1690 and in 1701, but according to some accounts his only comments were to complain about a cold draught in the chamber and request that the window be closed.[28]

Newton moved to London to take up the post of warden of the Royal Mint in 1696, a position that he had obtained through the patronage of Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax, then Chancellor of the Exchequer. He took charge of England's great recoining, somewhat treading on the toes of Master Lucas (and securing the job of deputy comptroller of the temporary Chester branch for Edmond Halley). Newton became perhaps the best-known Master of the Mint upon Lucas' death in 1699, a position Newton held until his death. These appointments were intended as sinecures, but Newton took them seriously, retiring from his Cambridge duties in 1701, and exercising his power to reform the currency and punish clippers and counterfeiters. As Master of the Mint in 1717 in the Law of Queen Anne Newton unintentionally moved the Pound Sterling from the silver standard to the gold standard by setting the bimetallic relationship between gold coins and the silver penny in favour of gold. This caused silver sterling coin to be melted and shipped out of Britain. Newton was made President of the Royal Society in 1703 and an associate of the French Acadmie des Sciences. In his position at the Royal Society, Newton made an enemy of John Flamsteed, the Astronomer Royal, by prematurely publishing Flamsteed's Historia Coelestis Britannica, which Newton had used in his studies.[29]

In April 1705 Queen Anne knighted Newton during a royal visit to Trinity College, Cambridge. The knighthood is likely to have been motivated by political considerations connected with the Parliamentary election in May 1705, rather than any recognition of Newton's scientific work or services as Master of the Mint.[30]

Newton died in London on 31 March 1727 [OS: 20 March 1726][1], and was buried in Westminster Abbey. His half-niece, Catherine Barton Conduitt,[31] served as his hostess in social affairs at his house on Jermyn Street in London; he was her very loving Uncle,[32] according to his letter to her when she was recovering from smallpox. Newton, who had no children, had divested much of his estate onto relatives in his last years, and died intestate.

After his death, Newton's body was discovered to have had massive amounts of mercury in it, probably resulting from his alchemical pursuits. Mercury poisoning could explain Newton's eccentricity in late life.[33]

After death

Fame

French mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange often said that Newton was the greatest genius who ever lived, and once added that he was also the most fortunate, for we cannot find more than once a system of the world to establish.[34] English poet Alexander Pope was moved by Newton's accomplishments to write the famous epitaph:

Nature and nature's laws lay hid in night;

God said Let Newton be and all was light.

Newton himself was rather more modest of his own achievements, famously writing in a letter to Robert Hooke in February 1676:

If I have seen further it is by standing on ye shoulders of Giants[35]

though historians generally think the above quote was an attack on Hooke (who was short and hunchbacked), rather than or in addition to a statement of modesty.[36][37] The two were in a dispute over optical discoveries at the time. The latter interpretation also fits with many of his other disputes over his discoveries, such as the question of who discovered calculus as discussed above.

In a later memoir, Newton wrote:

I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-s , and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.[38]

Commemorations

Newton statue on display at the Oxford University Museum of Natural HistoryNewton's monument (1731) can be seen in Westminster Abbey, at the north of the entrance to the choir against the choir screen. It was executed by the sculptor Michael Rysbrack (16941770) in white and grey marble with design by the architect William Kent (16851748). The monument features a figure of Newton reclining on top of a sarcophagus, his right elbow resting on several of his great books and his left hand pointing to a scroll with a mathematical design. Above him is a pyramid and a celestial globe showing the signs of the Zodiac and the path of the comet of 1680. A relief panel depicts putti using instruments such as a telescope and prism.[39] The Latin inscription on the base translates as:

Here is buried Isaac Newton, Knight, who by a strength of mind almost divine, and mathematical principles peculiarly his own, explored the course and figures of the planets, the paths of comets, the tides of the sea, the dissimilarities in rays of light, and, what no other scholar has previously imagined, the properties of the colours thus produced. Diligent, sagacious and faithful, in his expositions of nature, antiquity and the holy Scriptures, he vindicated by his philosophy the majesty of God mighty and good, and expressed the simplicity of the Gospel in his manners. Mortals rejoice that there has existed such and so great an ornament of the human race! He was born on 25 December 1642, and died on 20 March 1726/7. Translation from G.L. Smyth, The Monuments and Genii of St. Paul's Cathedral, and of Westminster Abbey (1826), ii, 7034.[39]

From 1978 until 1988, an image of Newton designed by Harry Ecclestone appeared on Series D 1 banknotes issued by the Bank of England (the last 1 notes to be issued by the Bank of England). Newton was shown on the reverse of the notes holding a book and accompanied by a telescope, a prism and a map of the Solar System.[40]

A statue of Isaac Newton, standing over an apple, can be seen at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

Newton in popular culture

Main article: Isaac Newton in popular culture

Religious views

Main article: Isaac Newton's religious views

Newton's grave in Westminster Abbey.Historian Stephen D. Snobelen says of Newton, Isaac Newton was a heretic. But ... he never made a public declaration of his private faith which the orthodox would have deemed extremely radical. He hid his faith so well that scholars are still unravelling his personal beliefs.[41] Snobelen concludes that Newton was at least a Socinian sympathiser ( *

royal28 16.07.09 - 08:09am *

*